Here are some Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Parkinson’s, the blog site, and possibly other topics! Select the topic you wish to view by using clicking on the topic header in the gray box; that will cause that topic to expand.

+ Parkinson’s Disease

Questions on Parkinson’s Disease

– What causes Parkinson’s Disease?

It is unclear what causes Parkinson’s. While some cases can be traced to a genetic mutation, the disease typically doesn’t run in families. Environmental factors, coupled with genetics, could play a role in the development of Parkinson’s.

Parkinson’s disease is caused by the progressive impairment or deterioration of neurons (nerve cells) in an area of the brain known as the substantia nigra. When functioning normally, these neurons produce a vital brain chemical known as dopamine. Dopamine serves as a chemical messenger allowing communication between the substantia nigra and another area of the brain called the basal ganglia. This communication coordinates smooth and balanced muscle movement. A lack of dopamine results in abnormal nerve functioning, causing a loss in the ability to control body movements.

Courtesy of

– What are the stages of Parkinson’s Disease?

If you have Parkinson’s disease (PD), you may wonder how your condition will unfold. You might want to know what symptoms you might have, when they’ll start, and how they’ll affect your life.

These are basic questions. But Parkinson’s is not a basic disease. It doesn’t move in a straight line, and it’s hard to pin down exactly how it’ll progress.

What Makes PD Hard to Predict

Parkinson’s comes with two main buckets of possible symptoms. One affects your ability to move and leads to motor issues like tremors and rigid muscles. The other bucket has non-motor symptoms, like pain, loss of smell, and dementia.

You may not get all the symptoms. And you can’t predict how bad they’ll be, or how fast they’ll get worse. One person may have slight tremors but severe dementia. Another might have major tremors but no issues with thinking or memory. And someone else may have severe symptoms all around.

On top of that, the drugs that treat Parkinson’s work better for some people than others. All that adds up to a disease that’s very hard to predict.

What You Can Expect

Parkinson does follow a broad pattern. While it moves at different paces for different people, changes tend to come on slowly. Symptoms usually get worse over time, and new ones probably will pop up along the way.

Parkinson’s doesn’t always affect how long you live. But it can change your quality of life in a major way. After about 10 years, most people will have at least one major issue, like dementia or a physical disability.

Motor Symptoms

You might break these into mild, moderate, and advanced stages. But any stage can have lots of gray areas. A tremor in your right arm may sound mild, but if you’re right-handed and it’s severe, it can affect your quality of life.

Mild stage. Symptoms are a bother, but they usually don’t stop you from doing most tasks. And drugs usually work well to keep them in check.

You might notice:

- Your arms don’t swing as freely when you walk

- You can’t make facial expressions

- Your legs feel heavy

- Posture becomes a little stooped

- Handwriting gets smaller

- Your arms or legs get stiff

- You have symptoms only on one side of your body, like a tremor in one arm

Moderate stage. Often within 3 to 7 years, you’ll see more changes. Early on, you might have a little trouble with something like buttoning a shirt. At this point, you may not be able to do it at all. You might also find that the medicine you take starts to wear off between doses.

You can expect:

- Changes in how you speak, like a softer voice or one that starts strong, but trails off

- Freezing when you first start to walk or change direction, as if your feet are glued to the ground

- Trouble swallowing

- Falls to be more likely

- Trouble with balance and coordination

- Slower movements

- Small, shuffling steps

Advanced stage. Some people never reach this stage. This is when medication doesn’t help as much and serious disabilities set in.

At this point, you likely:

- Are limited to bed or a wheelchair

- Can’t live on your own

- Have severe posture issues in your neck, back, and hips

- Need help with daily tasks

- Non-Motor Symptoms

Almost everyone with Parkinson’s gets at least one of these. When severe, they’re more likely than motor issues to lead to a disability or make you move into a nursing home. These symptoms can show up almost any time, but they follow a general trend.

What may show up early. You may have these issues years before any classic motor symptoms like tremors:

- Constipation

- Depression

- Loss of smell

- Low blood pressure when you stand up

- Pain

- Sleep issues

You also might get these symptoms later in the disease. And even if you have them, it doesn’t mean you have Parkinson’s. Scientists are still trying to understand the link. You might also have mild issues with thinking and planning, like forgetfulness, a shorter attention span, and a hard time staying organized. Drooling and a more urgent need to pee are also common.

What may show up later. Dementia and psychosis are two serious mental health issues that usually take a while to show up. Psychosis is a serious condition where you see or hear things that aren’t there, or believe in things that aren’t based in reality. Dementia means you can no longer think, remember, and reason well enough to carry on your normal life. As you age, you’re more likely to have both conditions the longer you have Parkinson’s.

Curtesy of

– What is Young-Onset Parkinson’s Disease?

About 10 to 20 percent of people with Parkinson’s experience symptoms before age 50, which is called “young onset.” While treatments are the same, younger people may experience the disease differently. Scientists are working to understand the causes behind young-onset Parkinson’s.

Diagnosis

People with young-onset Parkinson’s disease (YOPD) may have a longer journey to diagnosis, sometimes seeing multiple doctors and undergoing several tests before reaching a correct conclusion. As with Parkinson’s diagnosed later in life, YOPD is diagnosed based on a person’s medical history and physical examination. When younger people and their clinicians are not expecting Parkinson’s disease (PD), the diagnosis may be missed or delayed. It’s not uncommon for arm or shoulder stiffness to be attributed to arthritis or sports injuries before Parkinson’s is eventually diagnosed.

Causes

In everyone with Parkinson’s, both genetic changes and environmental factors likely contribute, to different degrees, to cause the disease. In younger people, especially those who have multiple family members with Parkinson’s, genetics may play a larger role. Certain genetic mutations (in the PRKN gene, for example) are associated with an increased risk of young-onset PD. If you have YOPD (and particularly if you have a family history of Parkinson’s), you may consider genetic testing to see if you carry one of these mutations. Testing can be done through your doctor’s office but mainly is done in clinical studies since results currently don’t change the medications you take. As part of research, genetic information offers valuable insights toward better understanding of the disease and potential therapies. Discuss the pros and cons with your family, your doctor and a genetic counselor.

Symptoms and Progression

People with YOPD are more likely to experience dystonia — prolonged muscle contractions that lead to abnormal postures, such as twisting of the foot. Also, younger people are more likely to develop dyskinesia — involuntary, uncontrolled movements, often writhing or wriggling — as a complication of long-term levodopa use combined with a long course of Parkinson’s disease.

Progression of disease over time is, in general, slower.

Treatment Options

Options for managing Parkinson’s symptoms are essentially the same no matter when Parkinson’s is diagnosed. To potentially delay dyskinesia, younger people may choose to postpone starting medication or begin with Parkinson’s drugs other than levodopa, especially if symptoms are mild and don’t interfere with work, physical or social activities. Options may be to start with an MAO-B inhibitor; amantadine; a dopamine agonist; or, when tremor is particularly prominent, an anticholinergic drug.

Medications used to treat PD

Physicians and researchers have long engaged in a healthy discussion over the best time to start levodopa. Some believe it’s better to start sooner to control symptoms, maximize quality of life and allow a person to remain active as long as possible. Others hold off to potentially delay motor complications, such as dyskinesia. Ask your physician for his or her take on this issue and consider the pros and cons of both approaches. Work closely with your movement disorder specialist to determine which medication is right for you and when.

Research into Young-onset PD

Scientists are studying the genetic connections to young-onset Parkinson’s disease, such as mutations in the PRKN and PINK1 genes, and other contributing factors. That information could lead to preventive strategies and treatments. Researchers also are working diligently to develop objective tests for Parkinson’s so the path to a confirmed diagnosis won’t be as long.

While participating in a clinical trial may be the furthest thing from one’s mind when processing a YOPD diagnosis, many studies of therapies to slow or stop progression need people who were recently diagnosed and have not begun medication.

Courtesy of

– How is Parkinson’s Disease diagnosed?

Unlike many other disorders, medical tests and procedures cannot be used to diagnosis PD. Diagnosis is almost always based on a clinician’s physical examination. Again, diagnosis is typically made if an individual experiences two of the four chief symptoms (resting tremor, stiffness, slowness of movement and/or poor balance).

Once PD is suspected, medication therapy may be started depending on the severity of the symptoms. An individual’s response to anti-Parkinson medications is also a useful measure in confirming the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. If symptoms improve after starting these medications, PD is typically the appropriate diagnosis. If symptoms do not improve, other disorders, such as Parkinson-plus syndromes, should be considered.

Parkinson-plus syndromes include progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, and diffuse cortical Lewy body disease. There are many disorders that can cause Parkinson-like symptoms and therefore, a thorough history and exam is essential during the diagnostic process.

– How is Parkinson’s Disease treated?

At this time, there is no known cure for Parkinson’s disease. Medications are used to treat the symptoms of PD, and are the most useful form of treatment. PD medications include:

- – Carbidopa/Levodopa (Sinemet)

- – Pramipexole (Mirapex)

- – Pergolide (Permax)

- – Ropinirole (Requip)

- – Bromocriptine (Parlodel)

- – Entacapone (Comtan) –

- – Amantadine (Symmetrel)

- – Selegiline (Eldepryl)

- – Rasagiline (Azilect)

- – Opicapone (Ongentys)*

- – Istradefylline (Nourianz)*

- – Carbidopa/Levodopa inhalation powder (Inbrija)*

* Newer Med

These medications can be used in various combinations and typically provide good symptom management. Unfortunately, as PD progresses, complications of these medications become more likely and often very troublesome. Such complications can include dyskinesias (involuntary writhing movements of the body), hallucinations (seeing things that are not real), and motor fluctuations (wearing off of medications).

Surgical procedures are also available and become a valuable option when the above medication complications are difficult to manage. These options include:

Courtesy of the US Government websites

– Is Parkinson’s disease fatal?

I know a lot of folks who ask this question; and sometimes I even ask myself! I always now say that, despite common misconceptions, Parkinson’s disease itself doesn’t shorten one’s life expectancy. However, there are things, especially in the late stages of the disease, that can put one at a higher risk for fatal complications – things like: poor balance (i.e. falls causing fractured hips), immobility, and difficulty swallowing, which can lead to pneumonia and choking.

– “l keep losing weight (that I don’t want to lose). What’s happening and what can I do about it?”

Weight loss is a common side effect of Parkinson’s. In fact, in many cases, weight loss precedes motor symptoms and is considered an index for Parkinson’s progression. There are a variety of potential causes at play such as overall malnutrition, increased energy output and decreased energy input and problems with nausea or vomiting and lack of appetite.

The best thing to do if you have unwanted weight loss is to talk to your doctor about creating a plan to manage your caloric intake. Creating a meal plan to gain and then maintain your weight will vary by individual, but shakes, smoothies, nuts and seeds are all simple ways to consider adding nutritional calories to your diet. If loss of smell is a problem for you, you can also consider using more spices to make your food taste better.

Courtesy of

– How Can I Better Cope With Having Parkinson’s Disease?

Trust me, I know that it it rough to take in the knowledge that you have Parkinson’s, and then having to live with it each day. So here are some things I’ve found that you can do to help yourself better cope with having PD:

- Find out as much as you can about your illness. Take action early so you can understand better what is happening to you.

- Talk to your friends and family about it. Don’t isolate them – remember, they are there to help you!

- Talk with your doctor, nurse, or other health care provider about your disease. Make sure they repeat any instructions or medical terms that you don’t understand or remember.

- Make use of the many resources and support services offered to you, both locally and online.

- Continue to do things you enjoy. Try to have fun!

- Learn to manage stress.

- Try to maintain a positive physical, emotional, and spiritual outlook on life.

- Your faith is important during this time! Pray, go to church, ask for help and prayer from your clergy and church members.

Lastly – and most important – REMEMBER THAT YOU ARE NOT ALONE! There are millions of us with Parkinson’s who are ready to help!

– I Often Have “Freezing” Spells. What Can I Do to Keep Moving?

If you have trouble with “freezing” in place:

- – Rock from foot to foot to get moving again.

- – Have someone place their foot in front of you, or visualize something you need to step over, to get moving again.

Courtesy of

– “If I Take Regular Doses of Carbidopa/Levodopa, Should That Impact When And What I Should Eat?”

Yes. The effect of levodopa may be influenced by proteins in food. Proteins can compete with levodopa uptake both from the gut and across the blood-brain barrier and may, therefore, inhibit the effect of levodopa. Therefore, if you take regular doses of carbidopa or levodopa, you should talk to your doctor about taking your medicine 30-60 minutes before eating, especially before high protein meals. Protein, however, is still important for your diet so it can be helpful to create a schedule to manage your medication and protein intake throughout the day so that you’re not eating your high protein meals simultaneously with your carbidopa/levodopa.

Courtesy of

Courtesy of

– “I’m Constipated All The Time. Is There Anything I Can Do?”

Constipation is the most common gastrointestinal problem for people with Parkinson’s. Increasing the amount of water you drink and your fiber intake are two things you can do to try and improve symptoms of constipation. Most experts recommend at least six to eight glasses of fluid a day, and some recommend prune juice as an excellent way to increase fluid intake and relieve constipation. Increasing the number of high fiber fruits like apples, prunes, dates, figs, radishes, berries, nuts and beans and insoluble fiber from whole grains like brown rice and rye can also help relieve your constipation. Remember that introducing additional fiber should be done slowly to allow for your digestive system to adjust to the effects.

Courtesy of

+ Deep Brain Stimulation

Common questions about DBS…

– What is Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)?

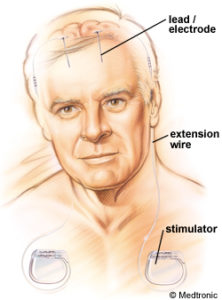

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) uses electrical stimulation to treat neurological conditions such as Parkinson disease (PD), essential tremor, and multiple sclerosis. DBS is used to treat movement problems such as tremors, stiffness, difficulty in walking, and slowed movement. While it does not cure these conditions, DBS can ease symptoms and decrease the amount of medicine you need.

In DBS surgery, electrodes are inserted into a targeted area of the brain, using MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and recordings of brain cell activity during the procedure. A second procedure is performed to implant an IPG, impulse generator battery (like a pacemaker). The IPG is placed under the collarbone or in the abdomen. The IPG provides an electrical impulse to a part of the brain involved in motor function. Those who undergo DBS surgery are given a controller to turn the device on or off.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery was first approved in 1997 to treat Parkinson’s disease (PD) tremor, then in 2002 for the treatment of advanced Parkinson’s symptoms. More recently, in 2016, DBS surgery was approved for the earlier stages of PD — for people who have had PD for at least four years and have motor symptoms not adequately controlled with medication.

COURTESY OF PARKINSON’S FOUNDATION

– What PD symptoms respond to DDS?

DBS is certainly the most important therapeutic advancement since the development of levodopa. It is most effective for people who experience disabling tremors, wearing-off spells and medication-induced dyskinesias, with studies showing benefits lasting at least five years. That said, it is not a cure and it does not slow PD progression. It is also not right for every person with PD. It is not thought to improve speech or swallow issues, thinking problems or gait freezing.

– What are the risks of having DBS surgery?

Although deep brain stimulation is generally considered to be low risk, any type of surgery has the risk of complications. Also, the brain stimulation itself can cause side effects.

Surgery risks

Deep brain stimulation involves creating small holes in the skull to implant the electrodes into the brain tissue as well as performing surgery to implant the device that contains the batteries under the skin in the chest. Complications of surgery may include:

- Misplacement of leads

- Bleeding in the brain

- Stroke

- Infection

- Breathing problems

- Nausea

- Heart problems

- Seizure

Possible side effects after surgery

Side effects associated with deep brain stimulation may include:

- Seizure

- Infection

- Headache

- Confusion

- Difficulty concentrating

- Stroke

- Hardware complications, such as an eroded lead wire

- Temporary pain and swelling at the implantation site

A few weeks after the surgery, the device will be turned on and the process of finding the best settings for the patient begins. Some settings may cause side effects, but these often improve with further adjustments of their device.

– What Is the prognosis once the surgery is complete?

Although most people still need to take medication after undergoing DBS, many people experience considerable reduction of their PD symptoms and can greatly reduce their medications. Then amount of reduction varies from person to person.

The reduction in dose of medication leads to decreased risk of side effects such as dyskinesia (involuntary movements of the arms, legs and head). There is a one to three percent chance of infection, stroke, cranial bleeding or other complications associated with anesthesia, per side that is done. It is best to discuss associated risks with your neurologist and neurosurgeon.

– Who is a Good Candidate for DBS?

For the most part, here are the guidelines used in determining if an individual is a good candidate for DBS surgery:

- You have had PD symptoms for at least five years.

- You have “on/off” fluctuations despite consistent and regular medication dosing.

- You have dyskinesias.

- You are unable to tolerate anti-Parkinson’s medications due to side effects.

- You have tremor that is not well controlled with medication (even with medical management by a movement disorders specialist).

- You continue to have a good response to PD medications, especially carbidopa/levodopa, although the duration of response may be insufficient.

- You have tried different combinations of anti-Parkinson’s medications under the supervision of a movement disorders neurologist.

- You have PD symptoms that interfere with daily activities.

COURTESY OF PARKINSON’S FOUNDATION

– When is it too late for DBS?

One of the questions posed to me recently has been, ‘When is the best time to have DBS? And when is it too late?“

Well, the FDA recently changed their approval for DBS, now making it available for those who have been diagnosed (or had symptoms) for at least 4 years. Previous to this, I think it used to be 6-8 years. But it is now be recognized that having DBS earlier may actually be better; because the earlier DBS is introduced – the greater the benefits.

Anyway, according to the doctors, in order to even consider DBS:

- You must have symptoms for at least 4 years;

- Have responded well to the medication levodopa;

- Still benefit from medication, but it’s becoming less effective or causing intolerable side effects;

- Require multiple medications, higher dosages, or more frequent doses to manage your symptoms.

- Ability to remain calm and cooperative during an awake neurosurgical procedure lasting 1-3 hours per brain side.

+ Deep Brain Thoughts Website

If you are experiencing any problems with the website (such as old items showing up or sections not showing up properly) try reloaded/refreshing the web page. This can usually be done by using the reload button (usually looks like a circular line with an arrow on the end) on your browser’s address bar. If that does not work, then try flushing your browser’s cache memory area. This can fix a lot of these issues.

Below are links for flushing cache on the various major browsers available: